Forty-six percent of new employees will fail within 18 months of hire. Eighty-nine percent of the time it’s for attitude, and low emotional intelligence ranks second in why they fail.

People low in emotional intelligence don’t understand or know how to manage their own emotions. And they don’t know how to read emotions in others. We see this in employees who struggle to deal with stress, overcome obstacles and resolve conflict, or who fail to meet the needs of coworkers and customers, are negative, blamers, entitled, procrastinators, change resistors, overly sensitive or drama kings and queens. And that’s just for starters.

You’ve got limited time when interviewing candidates and it isn’t easy to assess emotional intelligence. But with a good interview question or two and the knowledge of what good and bad responses sound like, you can identify whether someone can move past negative feelings including anger, doubt and anxiety, or if they are generally flexible, optimistic, confident, empathic, congenial and more.

Interestingly, not all jobs require the same levels of emotional intelligence. Research shows that in certain jobs, having higher emotional intelligence is actually correlated with lower job performance. The determining factor in whether emotional intelligence is positively or negatively related to job performance is called “emotional labor.” You can actually test this for yourself in the online quiz “Does Your Job Require High Or Low Emotional Intelligence?”

Here are two interview questions to test emotional intelligence along with some real-life responses the questions generated. These questions work to reveal the truth about emotional intelligence because they are structured as non-leading and open-ended behavioral questions.

Question No. 1: Could you tell me about a time you made a mistake at work?

You won’t hear people low in emotional intelligence take much accountability for their mistakes. The people you want to hire know that it’s OK to make mistakes as long as they acknowledge the error, make corrections, help others to avoid making similar errors and move on. It should be easy to differentiate the good answer from the bad answer in the following real-life responses:

• Answer No. 1: I was told I generated a client report incorrectly, but I had done it that way before and no one ever said anything. After some research, I learned that the proper instructions were never written down anywhere and the person that instructed me to do it that way was no longer with the company. It made me mad and from that point on I always safeguarded myself so I never got blamed for someone else’s mistake again.

• Answer No. 2: There was a problem on the production line and I ordered a shut down on the whole system. It took hours to repair during which time I learned that one of my peers could have fixed the problem and minimized the impact of lost production. I made a hasty decision in response to feeling overwhelmed in the moment. I felt embarrassed to have failed to access all solutions and expertise available to me, but I learned a lot from the experience.

Question No. 2: Could you tell me about a time you got tough feedback from your boss?

Emotionally intelligent people are self-aware, self-confident and open-minded; they have a thick skin that allows them to receive and positively utilize critical feedback. People with low emotional intelligence typically get offended or defensive when presented with tough feedback. It’s not hard to identify the two in the following examples of real-life answers to this interview question:

• Answer No. 1: My boss blindsided me with a negative comment about my behavior. I confronted him about it and he was unable to give me examples of when this occurred so the issue was dropped. I was livid about this and felt that it should have been removed from my performance review because it was unsubstantiated.

• Answer No. 2: After spending substantial time preparing to lead a training session, my manager told me I went into too much detail and didnt keep the presentation at a high enough level. The feedback came as a surprise, and I was disappointed, but it was valuable information. I had failed to build the training session to the audience and curb some of the unnecessary detail, and I corrected this in future sessions.

You can use these questions in your own interviews, or look for situations where emotional intelligence (or a lack of it) reveals itself in your organization to create new questions.

It’s also important to listen to how candidates respond. Do they rush in with the first thing that comes to mind, or do they take some time to answer tough questions, and how comfortable are they in that silence? People with good emotional intelligence also tend to have a well-developed emotional vocabulary. Everyone experiences emotions, but not everyone can accurately identify them when they occur. Take note whether candidates say they felt “good” or “bad” or if they use more specific words like “frustrated,” “anxious,” “excited” and “surprised” to express how they felt. A candidate’s word choice can provide good insight into whether they understand how they were feeling, how others felt, what caused a situation, and how this understanding directed them to act.

Mark Murphy is a NY Times bestseller, author of Hiring For Attitude, and founder of the leadership training firm Leadership IQ.

IQ Test Explained! With Answers and Solutions!

Your CartYour Shopping Cart is empty.

So much has been written about leadership personality and style that hiring managers are in danger of neglecting the most critical factor in executives’ success: intelligence. More specifically, those responsible for hiring and promoting haven’t been given the tools necessary to evaluate the cognitive abilities that allow a person to consistently reach the “right” answer. How could they recognize such smarts? Historically, the only reliable measure of such brainpower has been the standard IQ test, which, for good reasons, is rarely used in business settings. But in rejecting IQ testing altogether, hiring managers have turned their backs on the single most effective assessment of cognitive abilities, simply because there isn’t a version that applies to the corporate world. They have dismissed the one method that could help them identify business stars.

Yes, it’s nice when a leader is charismatic and confident, and a great résumé can tell you a lot about a person’s knowledge and experience. But such assets are no substitute for sheer business intelligence, and they reveal very little about the leader’s ability to get to the truth of the matter. Thinking critically is the primary responsibility of any manager, in any organization, and a leader’s capacity to engage in this process is largely determined by his or her intelligence. Of course, there are many academically brilliant people who might score in the genius range on an IQ test but who could never make it as the CEO of a Fortune 500 company. That’s not surprising, since IQ tests focus on the cognitive skills central to success in school, not success in business.

Nevertheless, there’s a lesson to be learned from the predictive power of IQ tests. That is, to accurately forecast how successful someone will be in a particular activity, you must examine the cognitive skills he or she possesses that directly affect that activity—in this case, in the workplace rather than in the classroom. In this article, I’ll define the specific cognitive abilities that make up what I call “executive intelligence” and describe what to look for when interviewing job candidates or considering a manager for promotion.

The Main Ingredient: Critical Thinking

For many years, management scholars and practitioners have acknowledged that business leaders must be able to think critically. Lucent Technologies CEO Patricia Russo, who has led the company’s turnaround, described this ability to me as “clarity of thought.” The people who have it are rare, she said, but if you get a team of clear thinkers, “the possibilities are endless.” Avon CEO Andrea Jung made a similar observation: “Clear thinking in senior leadership is a primary attribute we look for. I’ve seen little correlation between those who have a formal business education and those who possess clear thinking.…Some people have a knack for this, some don’t.” What Russo and Jung are referring to is a very specific ability—critical business thinking, which is the foundation of executive intelligence.

To better understand this concept, it’s useful to consider a business decision that could have benefited from some solid critical thinking. Let’s look at the introduction of the Segway Human Transporter. The upright powered vehicle was heralded by its inventors as the catalyst for a revolution in human mobility. But despite the hype, the Segway got a lukewarm reception from consumers and has not transformed urban transportation. Could the inventors have anticipated this outcome? A critical thinker might have analyzed the Segway’s market potential like this:

The motorized scooter has been around for a while, is functionally similar to the Segway, and sells for a fraction of the cost. Yet motor scooters have not been widely adopted, and cities have not altered their infrastructures to accommodate this mode of transportation. So why would the Segway succeed where the scooter has failed? The Segway has two advantages over the scooter: Users can stand and balance completely upright while the transporter is moving or stopped, and they can go backward. The basic question remains, though: Did the lack of these two features keep the scooter from being more widely adopted? If not, there is little reason to anticipate any greater demand for the Segway than there has been for the scooter. In fact, because of the Segway’s dramatically higher cost, there may be less demand.

The Segway is fun. But is it worth the cost? Not according to the market. The minds behind the Segway may be sophisticated and technologically brilliant, but they appear to be somewhat naive when it comes to business. Perhaps their excitement over the technology clouded their ability to challenge their market assumptions to any significant degree.

The Segway example is notable because it reveals a fundamental flaw in a company’s business plan. But it isn’t enough to look generally at what went well or poorly with a particular business. To hire potential business stars, we need to understand the basic attributes that lead individuals to make good or bad decisions. We need to understand what constitutes executive intelligence.

In school, students focus on “subjects”—history, math, language, and so on. Similarly, we can identify the subjects of executive work and the distinct set of aptitudes that a manager must be able to demonstrate in each. All managerial work falls into one of three subjects: accomplishing tasks, working with and through others, and judging oneself and adapting one’s behavior accordingly. (For a description of the research supporting these classifications, see the sidebar “Creating a Measure of Executive Intelligence.”) Here’s how executive intelligence is manifest within these three subjects.

When Alfred Binet was commissioned 100 years ago to create a measure of academic intelligence, he identified the school subjects that students needed to learn, such as arithmetic and language. Then he set about identifying which cognitive skills determined a student’s aptitude for mastering each of these subjects. His work formed the basis for what is known today as the IQ test, still recognized as the most powerful predictor of a child’s academic potential. While we accept that there is a set of cognitive skills that constitute academic intelligence, until now we have assumed that there is no such thing as intelligence unique to executives—that no distinctive set of cognitive skills determines business or leadership aptitude.

Yet, given the research, a defined set of cognitive skills clearly exists. What was needed was a test that could isolate these skills. Following Binet’s lead, I set about creating a measure of business intelligence.

The first step was to identify the “subjects” of executive work, which, based on a review of management and psychology literature, were accomplishing tasks, working with and through others, and judging oneself and adapting one’s behavior accordingly. These three broad categories cover all managerial responsibilities. For instance, making strategy decisions, determining business focus, providing direction, and implementing new initiatives all require the cognitive skills necessary to accomplish tasks. Anticipating and managing conflicts, leading teams, and handling customers and investors all require cognitive skills regarding relationships with people. Integrating others’ views, recognizing one’s changing circumstances, and adapting one’s behavior all require the use of cognitive skills having to do with self-awareness.

Next, I pulled together a list of the cognitive skills that had been cited by the most respected management scientists as being essential to effective leadership. Though the list was long, it was clear there was some repetition and overlap, so I needed to identify core aptitudes. I sorted the skills, and, interestingly, all of them fell naturally into the three categories. This confirmed that the three basic subjects of executive work were an accurate representation of real-world leadership.

The skills include such abilities as distinguishing primary goals from less relevant concerns, anticipating probable outcomes, and recognizing people’s underlying agendas. All of the cognitive skills determine how well someone gathers, processes, and applies information in order to identify the best way to reach a particular goal or navigate a complex situation. In other words, these are the skills that allow someone to achieve the highest level of critical thinking in the workplace.

To validate this theory of executive intelligence, I tested it against real-world executive performance, and a pattern became obvious: Star executives consistently outperformed their peers on these cognitive skills. What’s more, all of these aptitudes were necessary for effective decision making. Though most executives possess strong skills in one or two of the three subject categories, the stars of the business world show exceptional ability in all three.

In this subject, intelligent executives make decisions using a set of six core cognitive skills. Among them are critically examining underlying assumptions and identifying probable unintended consequences. (For the full list of cognitive skills in each subject, see the exhibit “The Skills That Make Up Executive Intelligence.”) With these aptitudes in mind, consider the way two CEOs accomplished tasks in response to a business crisis.

intelligent leaders:

appropriately define a problem and differentiate essential objectives from less-relevant concerns.

anticipate obstacles to achieving their objectives and identify sensible means to circumvent them.

critically examine the accuracy of underlying assumptions.

articulate the strengths and weaknesses of the suggestions or arguments posed.

recognize what is known about an issue, what more needs to be known, and how best to obtain the relevant and accurate information needed.

use multiple perspectives to identify probable unintended consequences of various action plans.

intelligent leaders:

recognize the conclusions that can be drawn from a particular exchange.

recognize the underlying agendas and motivations of individuals and groups involved in a situation.

anticipate the probable reactions of individuals to actions or communications.

accurately identify the core issues and perspectives that are central to a conflict.

appropriately consider the probable effects and possible unintended consequences that may result from taking a particular course of action.

acknowledge and balance the different needs of all relevant stakeholders.

intelligent leaders:

pursue feedback that may reveal errors in their judgments and make appropriate adjustments.

recognize their personal biases or limitations in perspective and use this understanding to improve their thinking and their action plans.

recognize when serious flaws in their ideas or actions require swift public acknowledgment of mistakes and a dramatic change in direction.

appropriately articulate the essential flaws in others’ arguments and reiterate the strengths in their own positions.

recognize when it is appropriate to resist others’ objections and remain committed to a sound course of action.

In the 1980s, General Motors was losing market share to its more efficient Japanese competitors, and, at the same time, it was struggling with terrible labor relations. Then-CEO Roger Smith developed a bold plan to solve both problems by replacing nearly all of GM’s manufacturing force with robotics. By the end of the 1980s, GM had spent more than $45 billion on plant automation—a sum that at the time would have been enough to purchase both Toyota and Nissan. Yet its market share and plant productivity continued to decline every year following automation. To Smith, automation had seemed like such a logical move and, obviously, such high-risk initiatives are very difficult to undertake. But Smith demonstrated a severe lack of executive intelligence in his analysis. First, he failed to question his underlying assumption that more robots equals cheaper cars. A review of readily available data would have revealed that machines entail huge capital expenses and call for highly skilled support technicians. Second, he failed to anticipate the unintended consequences of his initiative: Automation can severely limit a plant’s flexibility and, hence, its ability to change product lines. Had Smith more skillfully analyzed the situation, he might still have chosen to invest in automation, but he could have done so in a way that maximized his chances for success. As Robert Lutz, a senior GM executive, later explained, the best answer to GM’s productivity problems was, in fact, a combination of people and machines that capitalized on the strengths of each.

By contrast, when D. Keith Grossman was hired as Thoratec Corporation’s CEO in 1996, the medical devices company was struggling to survive. Grossman was charged with helping the company profitably produce and market its flagship product, a ventricular assist device for recovery from open-heart surgery. But Grossman was quick to question the industry’s fundamental assumption: that getting a successful product to market would result in a viable business. Thoratec was competing with large, global companies that were focused not just on a single device but on whole diseases, combining drugs and devices. What’s more, those firms had deep pockets to market to doctors and consumers.

Thoratec’s product-focused assumption had created an expensive unintended consequence: the need to build an infrastructure to produce and sell a single product, leading to a severe cost handicap since the same infrastructure would be required regardless of how many products the company was selling. Thoratec could never hope to compete with companies offering vast and integrated product lines. To succeed, Grossman concluded, the company would have to gain scale, either by acquiring another company or by being acquired. Grossman had effectively anticipated key obstacles to achieving the company’s objectives and identified sensible means to circumvent them, another of the cognitive skills required in accomplishing tasks.

Grossman’s articulation of his facts and conclusions was so sound in its logic that he was eventually able to convince the board of rival Thermo Cardiosystems—a company three times Thoratec’s size—to be acquired and even to accept as terms of the deal Thoratec’s stock and management team and a minority position on Thoratec’s board. Today, Thoratec is a thriving, highly profitable company with a virtual monopoly in its medical niche.

What shall we have for dinner this evening?

Don’t give an answer like “whatever you like”, “I don’t mind” ,“what would you like”, etc. This will hide your quality of leadership or taking stand, when your opinion is asked. This will show your willingness to take charge and when not.

IQ test questions and answers for job interview pdf

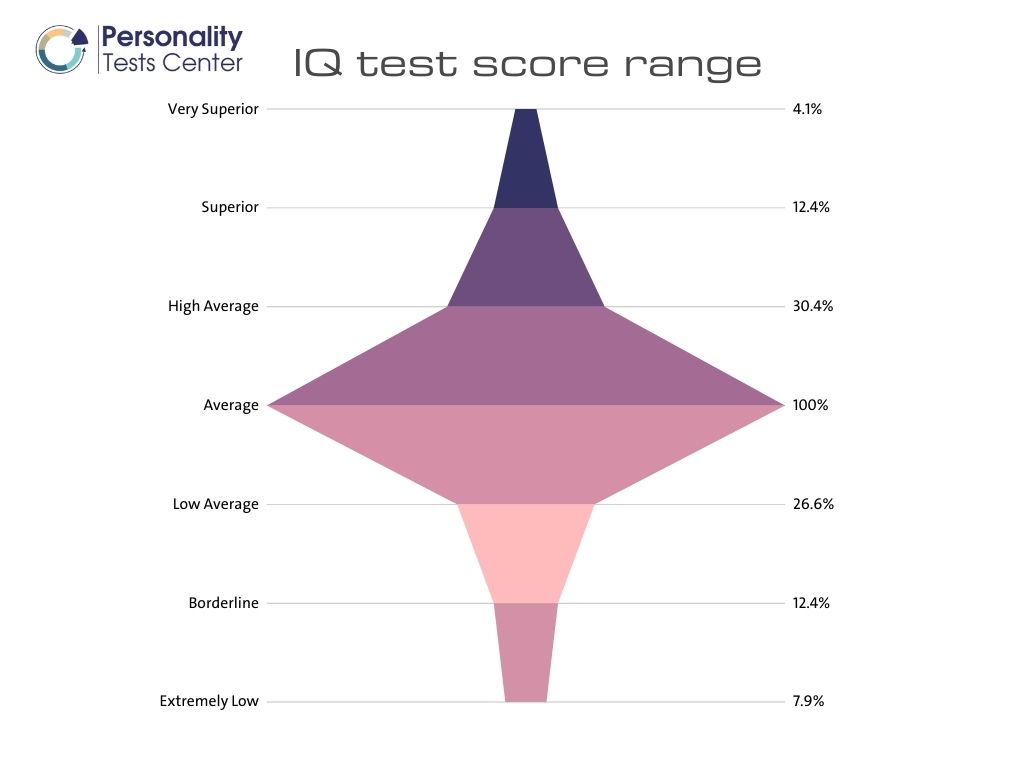

| IQ test range | IQ Classification | % of World Population |

| 130 and above | Very Superior | 2.1% |

| 121-130 | Superior | 6.4% |

| 111-120 | High Average | 15.7% |

| 90-110 | Average | 51.6% |

| 80-89 | Low Average | 13.7% |

| 70-79 | Borderline | 6.4% |

| Scores under 70 | Extremely Low | 4.1% |

Most iq tests score an individual on a scale of 100. The highest score possible is 145, and the lowest score possible is 61; scores between these two extremes represents just one standard deviation from the mean iq for that group.[5] For example, if you receive a score of 110 (a “superior” iq), this means your iq score was 10 points higher than the average person’s in that particular test sample. Likewise, if your scored 67 (an “average” iq), this means you were 11 points below the person mean.

FAQ

How do you test your intelligence in an interview?

What type of questions are on an intelligence test?

What are some intelligent questions to ask in an interview?

- What does “success” mean in this role? …

- Am I a good fit for the company? …

- What challenges did my predecessor face? …

- What was the last person in this role missing? …

- Do you have any doubts about my profile? …

- Where will this role go in the future? …

- What is the company culture like?

What are the 5 hardest interview questions?

- What is your greatest weakness?

- Why should we hire you?

- What’s something that you didn’t like about your last job?

- Why do you want this job?

- How do you deal with conflict with a co-worker?

- Here’s an answer for you.